A stone marker sits on the island of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean, site of China’s first Arctic research station. Image by Christopher Michel available at Flickr.com under CC license.

China in the Polar “Zone of Peace”

China’s potentially growing economic influence in the Arctic region has raised concerns amongst Arctic states and stakeholders. What kind of security risks for the Arctic states and peoples could accompany China’s regional engagement?

In the post-Cold War era, the Arctic region has often been viewed as an exceptional space, an international zone of peace. The contemporary regional governance structure does not touch upon traditional hard security matters: The Arctic Council, the key regional forum, focuses on sustainable development in the region and excludes military matters. Accordingly, “security” has been traditionally discussed in non-military terms, and climate change is usually defined as the key security issue in the post-Cold War Arctic, causing severe risks to the Arctic inhabitants, fauna and flora, as well as altering ecosystems globally.

Undoubtedly, these changes have far-reaching geopolitical and security impacts as well, and there is a need for a paradigm shift in international security in the era of climate change. What is new, however, is that there have been signs that traditional security issues are making a comeback in Arctic security discussions, especially due to the intensifying great power competition between the United States and Russia as well as the ongoing power transition between the United States and China.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently questioned the role and intentions of China and Russia in the Arctic. Public domain image by CIA available at Wikimedia Commons.

In particular, the speech by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at the Arctic Council’s meeting in Rovaniemi in May 2019 caused a great sensation amongst Arctic audiences.

Pompeo explicitly challenged the regional role and intentions of China and Russia in the Arctic. Moreover, President Donald Trump confirmed in August 2019 that he was interested in purchasing Greenland, an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark. Although Trump’s idea aroused responses that ran the gamut from outrage to howls of laughter, these two extraordinary incidents underline the geostrategic importance of the Arctic in current international affairs. They could be seen as the United States’ efforts to counterbalance China’s growing foothold in the Arctic region.

China Goes North

Although China’s Arctic engagement has made headlines only during recent years, China is not totally a newcomer to the region. In 1925, it signed the Svalbard Treaty, and in 1990, a Chinese scientist visited the North Pole for the first time. In 2004, China launched its first Arctic research station in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard.

Today, China also has a joint aurora observation station in Iceland and a land satellite receiving station in Sweden. In addition, Chinese scholars conduct polar research on board the icebreaker research vessels MV Xuelong and MV Xuelong 2 – the latter being the first icebreaker domestically built in China.

MV Xuelong a Chinese icebreaker, has been used by China to conduct polar research. Image by Bahnfrend available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

China’s political role in the Arctic continues to be rather limited. In 2013, it became an observer at the Arctic Council. This status grants it access to all activities of the Council but does not entitle it to partake in regional decision-making.

In January 2018, China published its first-ever official Arctic White Paper. The document stresses that the Chinese government respects the sovereign rights of the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States) in the region.

Interestingly, the White Paper defines China as a “near-Arctic state” which also has legitimate rights in the region – and suggests that the Arctic states should respect these rights, including the right to conduct scientific research, navigate, perform flyovers, fish, lay submarine cables and pipelines, and even explore and exploit natural resources in the Arctic high seas. In 2018, China joined the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean.

The White Paper defines China as a “near-Arctic state” which also has legitimate rights in the region – and suggests that the Arctic states should respect these rights.

To legitimate China’s Arctic engagement, China’s White Paper portrays the Arctic as a globally shared space, a community with a shared future for mankind. In this way, China seems to induce a discursive shift from the traditional, territorial definition of the Arctic to a more global understanding of the region. Yet these efforts may also fail due to intensifying great power politics in the Arctic.

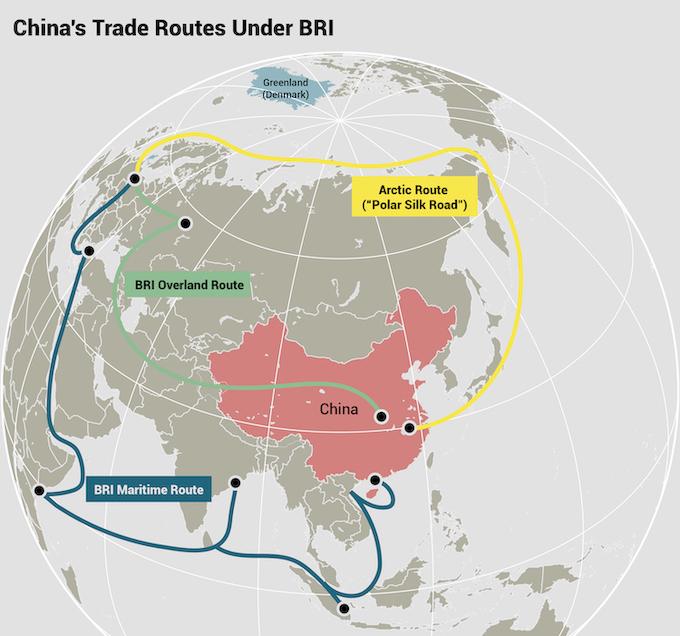

For the time being, China’s economic role in the Arctic also remains rather limited. In June 2017, the Arctic was incorporated in President Xi Jinping’s flagship project Belt and Road Initiative as one of the “blue economic passages”. China has also renamed the Arctic shipping lanes as the “Polar Silk Road.” Apart from its investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects in Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, most of the investment plans involving Chinese actors are at an initial stage. Nonetheless, the plans are plentiful: investments in energy and infrastructure projects, mining, and tourism in Russia and the Nordic countries, especially in Greenland. The future will tell whether these projects will be realised and what kind of political, economic, social and environmental impacts they have in the region.

As political and economic power tend to go hand in hand, China’s (potentially) growing economic influence in the Arctic region has not only created enthusiasm for economic possibilities for local companies but also raised various concerns amongst Arctic states and stakeholders, especially due to the poor track record of Chinese companies in other regions, such as Africa.

The Snowpanda House of Ähtäri Zoo in Finland. The zoo houses two pandas that arrived from China in January 2018, Pyry and Lumi. Image by Ninara posted available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

What kind of security risks for the Arctic states and peoples could accompany China’s regional engagement?

A Cold Reception

The military parade last month marking the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China made it clear that China has achieved significant strengthening and modernization of its military might. When it comes to the Arctic, however, there are no signs that China’s military presence in the region has in any way increased. It is a simple fact that the Arctic is not a core interest of the Chinese government. China has not made territorial claims in the Arctic, nor is it likely to make such claims in the future. Therefore, it is not meaningful to jump to the conclusion that China’s growing regional role will necessarily cause the “Arctic Ocean to transform into a new South China Sea, fraught with militarization and competing territorial claims,” as US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo anticipated in his speech in Rovaniemi, Finland, back in May this year.

That said, the US Department of Defence has justifiably warned about potential dual use of Chinese facilities in the Arctic – the danger that civilian research or the construction of critical infrastructure could serve China’s military intentions in the region. The Swedish Defence Agency has expressed similar concerns regarding the Chinese satellite station in Kiruna, the northernmost town in Sweden. It could be used, the agency said, to provide additional military satellite surveillance or complement Chinese military intelligence, for instance.

The city hall in Kiruna, Sweden, where the construction of a Chinese satellite station has prompted concern from the Swedish Defense Agency. Image by Johan Arvelius available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.