Twitter running on an iPhone. Image by Solen Feyissa available at Unsplash under CC license and recreated by Chabiński Michał.

Chinese Twiplomacy in the age of COVID-19

How effective is China’s twiplomacy in the global social media sphere? Studying the Twitter and Weibo accounts of five Chinese embassies in Europe revealed confusion and few coherent strategies.

Quick Take

-

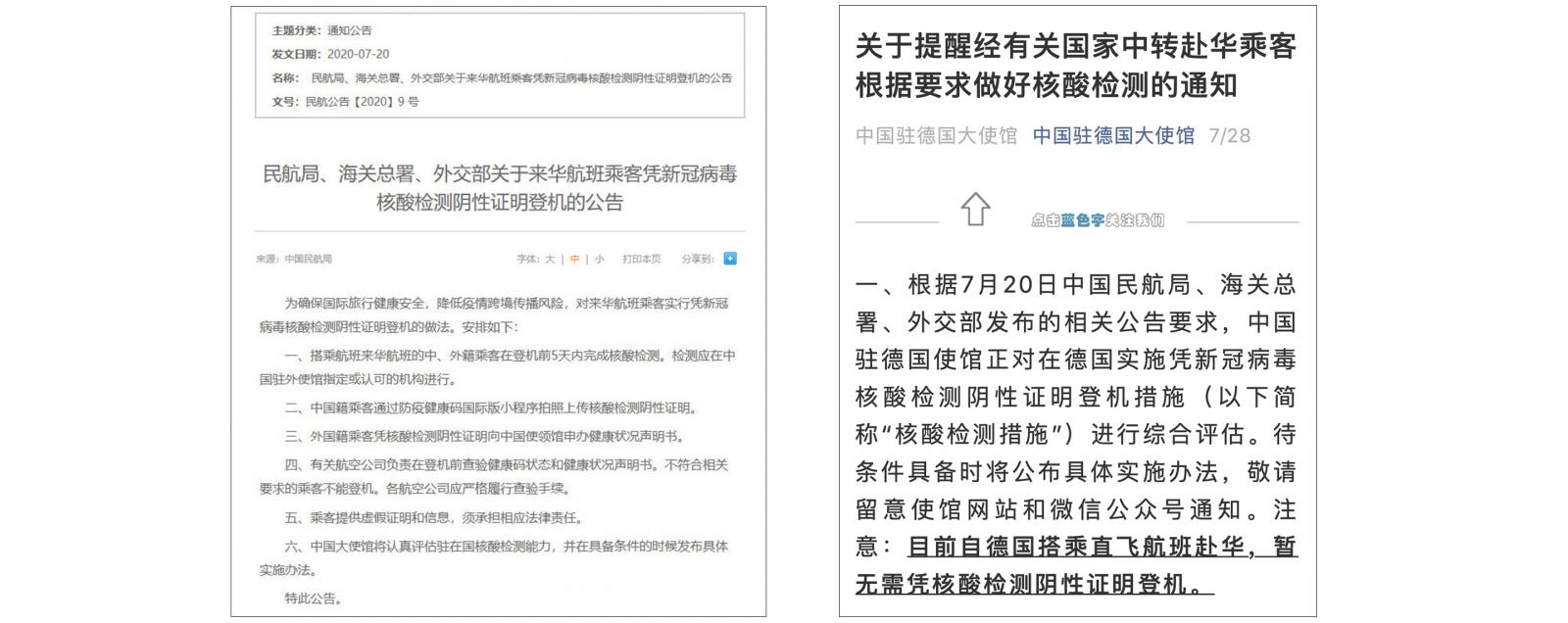

The COVID-19 crisis was the first chance for Chinese embassies in Europe to use their recently built social media presence.

-

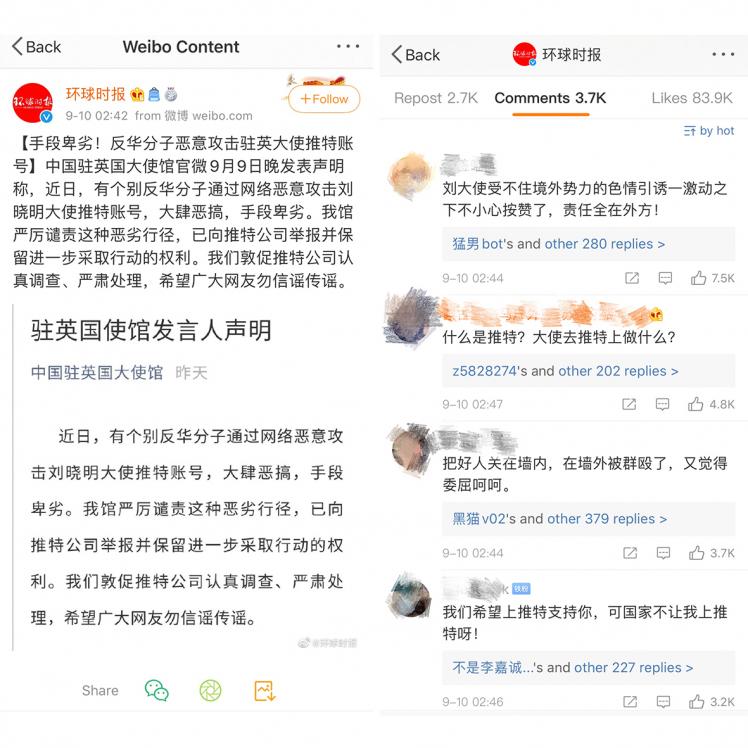

The aggressive “wolf warrior”-style communication strengthened support back home, but did not create positive outcomes in the non-Chinese social media sphere.

- At the height of the pandemic, Chinese diplomatic accounts did not primarily serve the purpose of supporting Chinese citizens in the EU with reliable information.

-

The data disprove the belief in China’s homogenous and effective foreign policy.

Since 2019, China has embraced Western social media in order to avoid being excluded from the global discussion. This approach in Chinese foreign policy can be linked to the general rise of “Twiplomacy” (the use of social media by diplomats to conduct diplomatic outreach), the perception that popular social media platforms can be used to combat negative narratives about China, and the shift to more aggressive practices, called “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” by Western observers.

In theory, performing public diplomacy via Twitter allows diplomats to directly reach local audiences and bypass local news media, which Chinese state media have called “China hating” for publishing unfavorable stories about the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Following the “Tell China’s stories well” (讲好中国故事) doctrine, put forward by Xi Jinping in the National Propaganda and Ideological Work Conference in August 2013, Chinese diplomats to the European Union took on a reactionary stance in order to protect the image of their home country. This ‘offensive’ of Chinese diplomats on social media is both a product of explicit instructions from above and bottom-up initiative to impress superiors within the Chinese party-state apparatus, according to a paper published by the Prague-based Association for International Affairs (AMO).

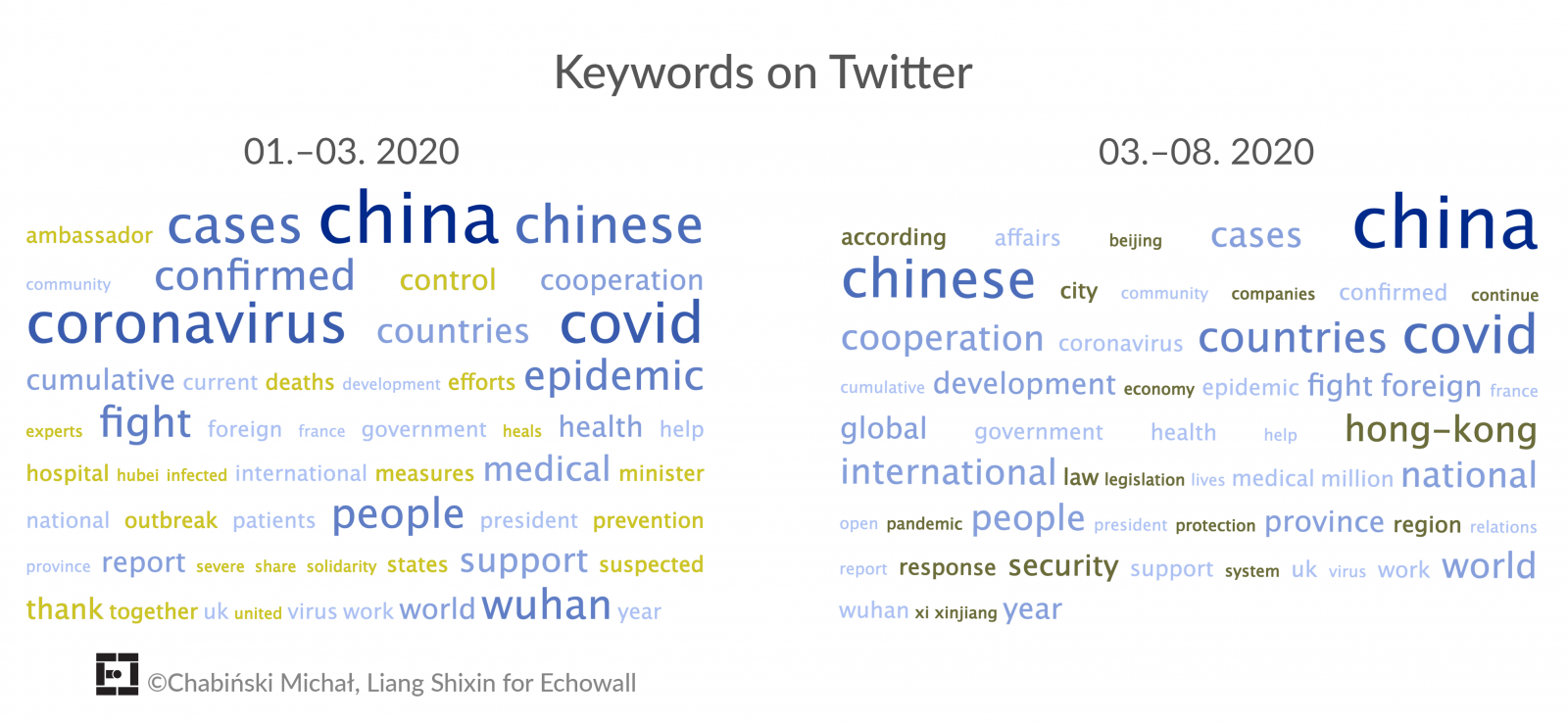

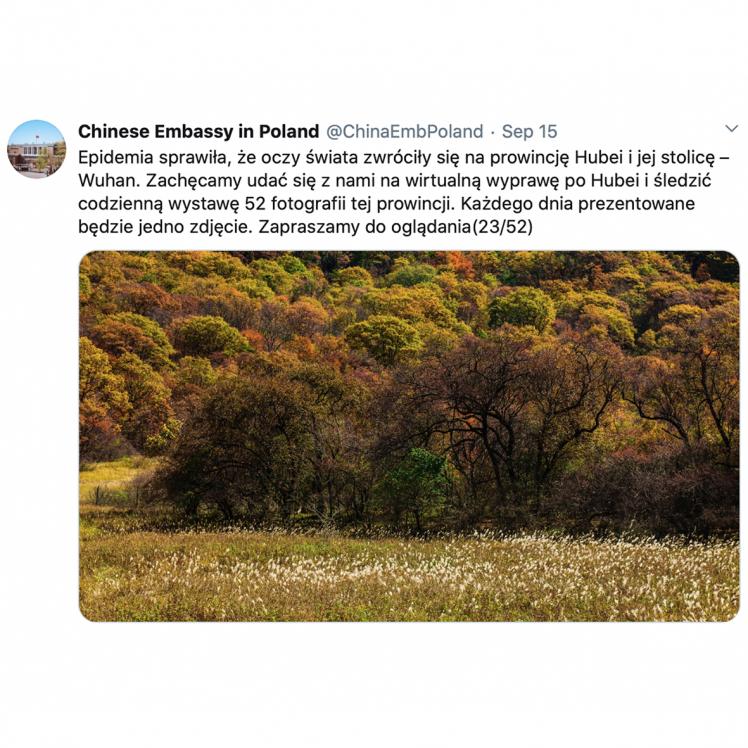

When the COVID-19 pandemic caused strict lockdowns and travel restrictions, an even greater share of international diplomatic activities moved online and social media became even more important for communicating foreign policy issues worldwide. In early 2020, Chinese diplomats in Europe significantly increased their activity on social media, with the intention of protecting China’s reputation, which had been undermined by the outbreak of the novel coronavirus that first appeared in the Chinese city of Wuhan. This was the first time Chinese diplomacy employed their newly built presence on Twitter to present, spread, and support their narratives outside of the country.

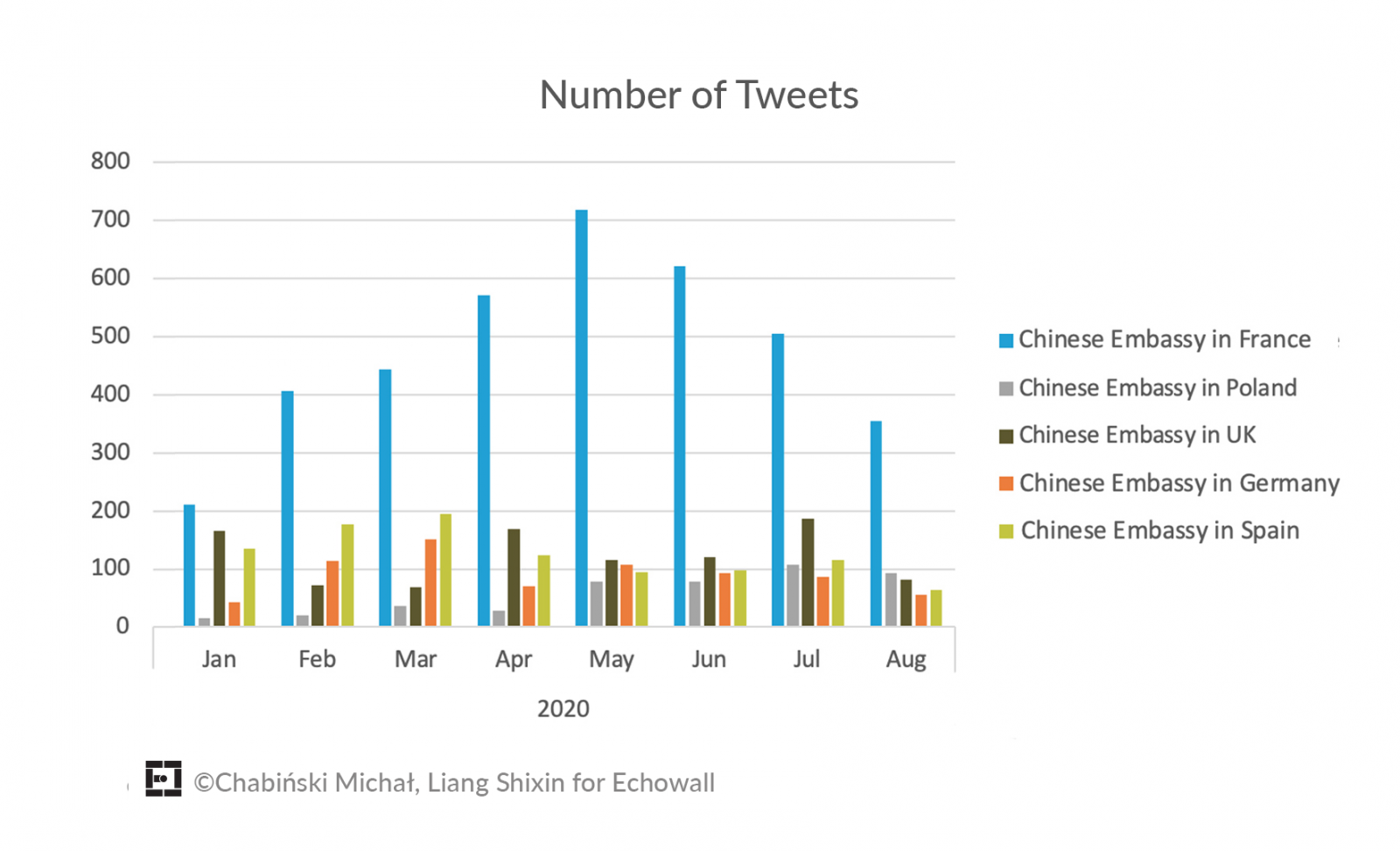

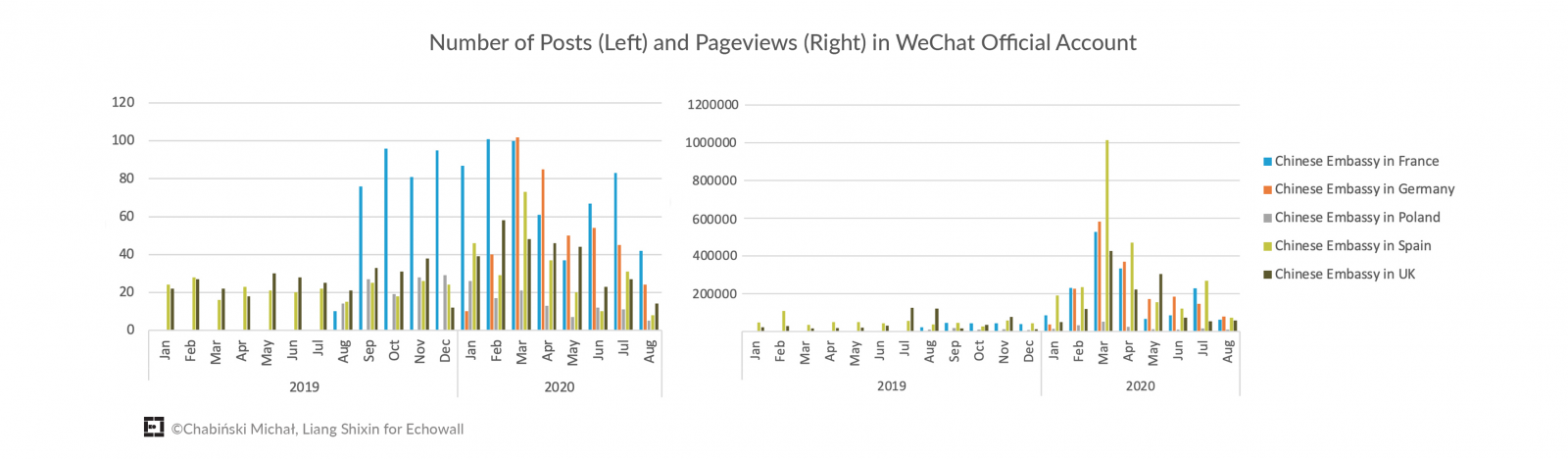

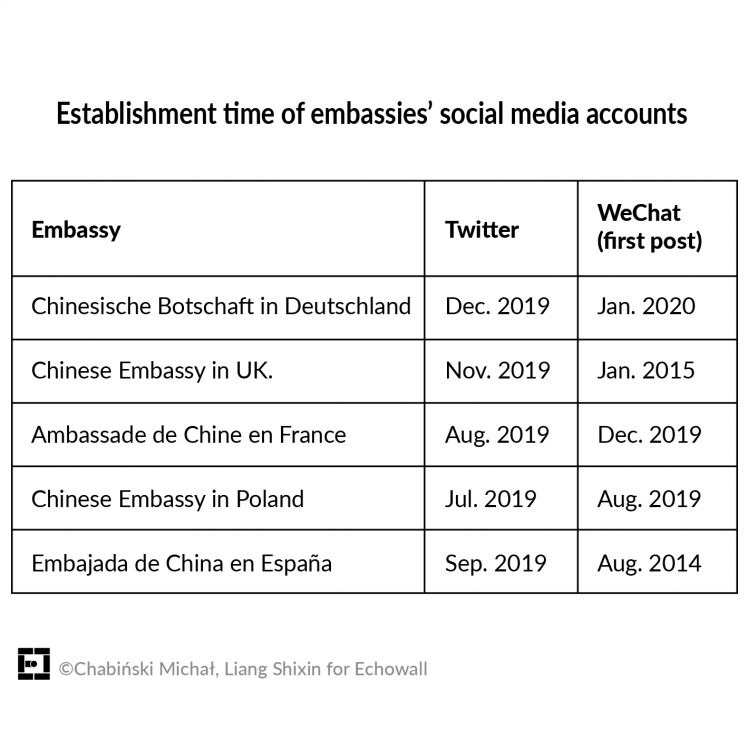

In this article we analyze the origins of Chinese diplomatic presence on social media and the effectiveness of these campaigns. We collected Tweets and WeChat posts from official accounts of five Chinese European embassies (Germany, United Kingdom, France, Poland, and Spain) in the period between December 2019 and August 2020. This study—based on 7,717 posts from Twitter and 1,813 posts from WeChat Public Accounts—aims to explain the structures behind their social media campaign and estimate the extent to which their efforts have had an impact on the perception of China among the EU member states and Chinese citizens at home.

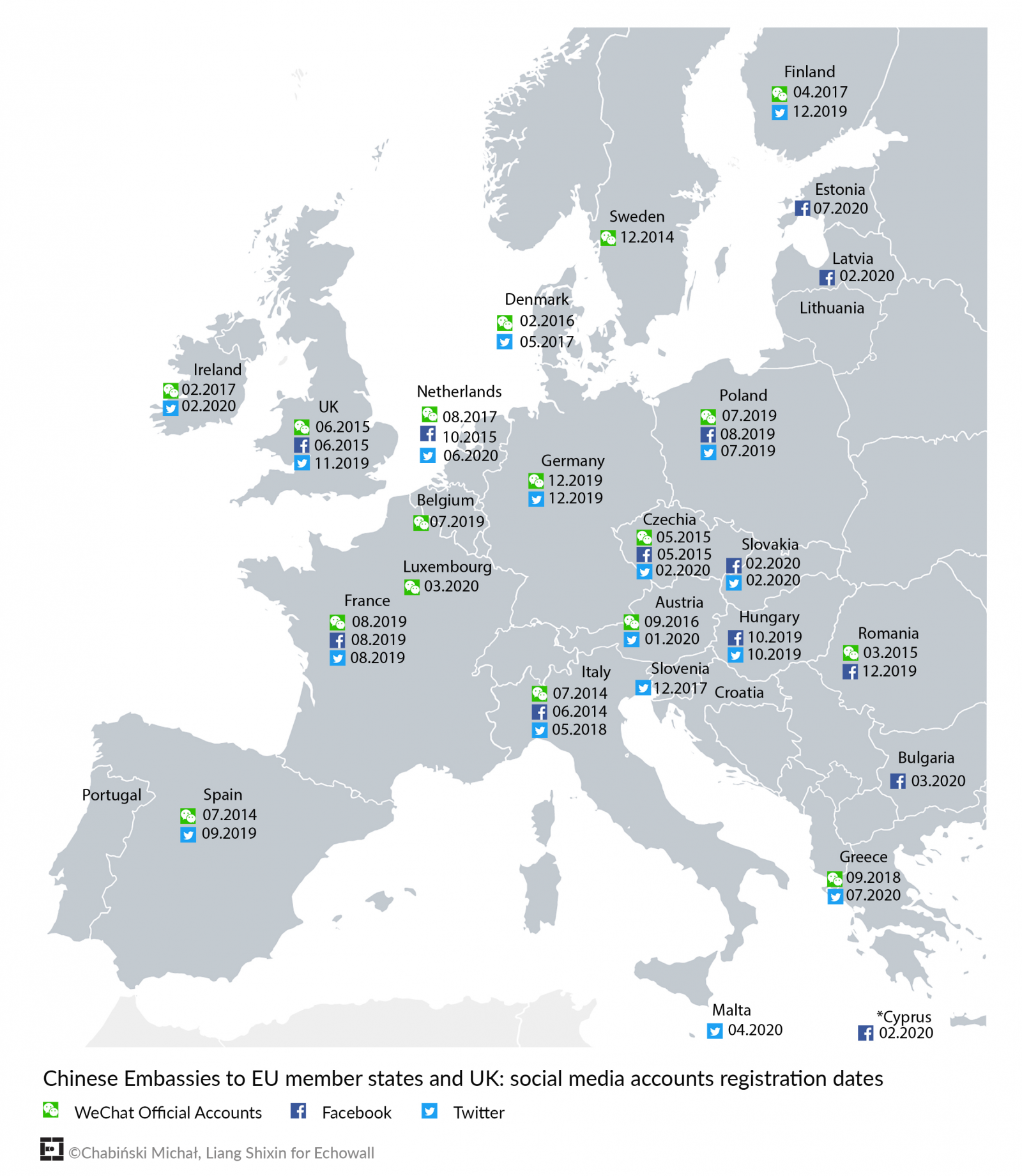

Chinese diplomacy on Twitter

Until mid-2019, only six of the Chinese embassies in the EU member states ran active accounts on EU’s widely popular social media platforms, Facebook or Twitter (both services are banned in China). By September 2020, 22 Chinese embassies to the EU and UK ran operational accounts on Twitter, Facebook, or both. The only EU countries where Chinese embassies do not have active social media accounts are Belgium, Croatia, Lithuania, Portugal, and Sweden. (The last one may come as a surprise, as China’s ambassador to Sweden, Gui Congyou, is well-known for sharp comments and for denouncing Swedish media as ‘anti-Chinese’.)

All of the Twitter accounts we analyzed were opened only in the second half of 2019. They have been active ever since, with the most active profile being that of the embassy to France, with an average of 390 tweets per month. The least active is the account of the embassy to Poland, with an average of 53 tweets per month.

The presence of Chinese institutions and politicians on Twitter and their engagement on the platform is diametrically different from their European or American counterparts. The biggest difference lies in the interactions patterns. Though the profiles of Chinese officials and institutions mainly like and reshare content from Chinese state-owned media, there is also a significant amount of interaction between, for example, journalists, or YouTube influencers.

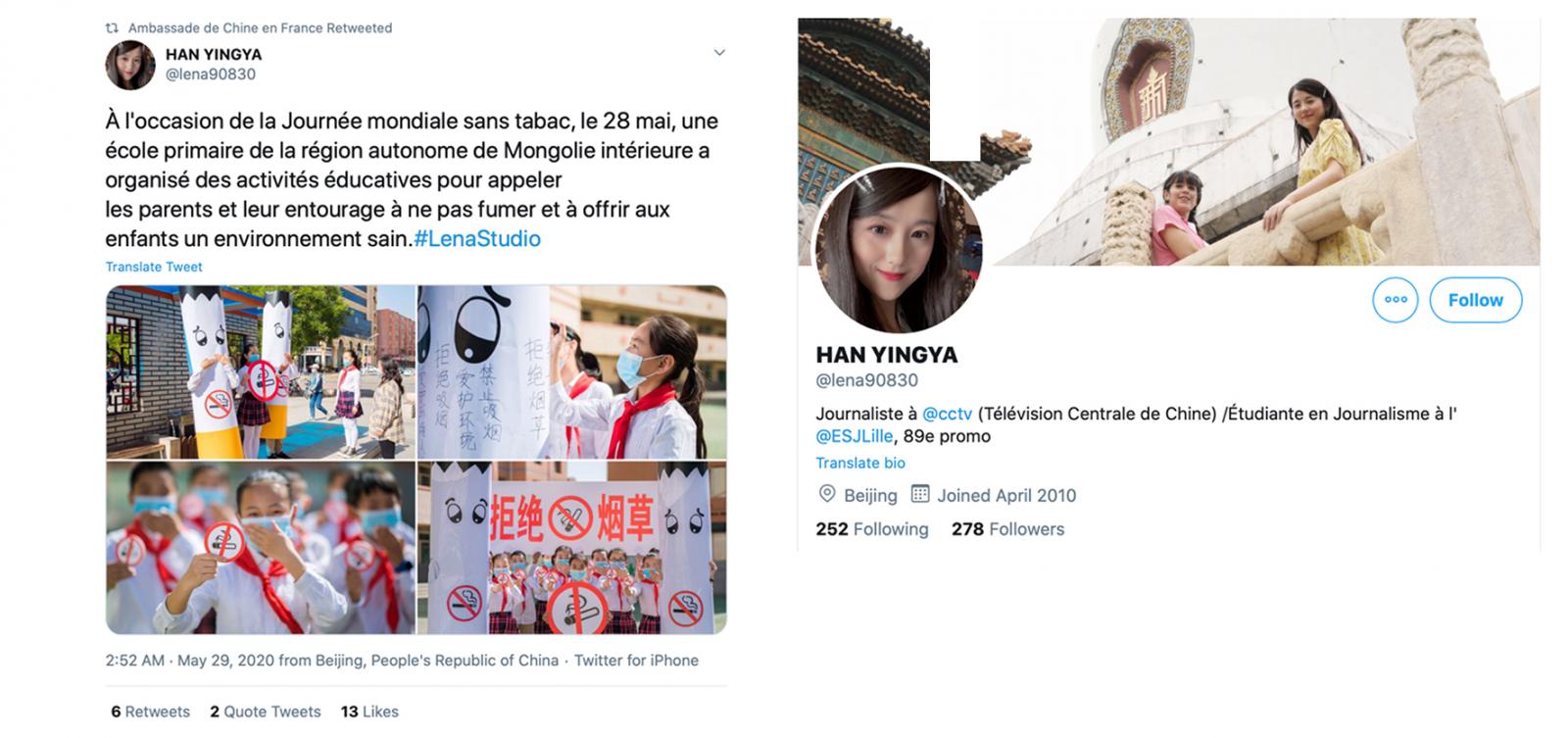

Take, for example, the account of the Chinese Embassy to France. The majority of retweets originate from state-owned media and from the French governmental accounts. However, the account also includes content from unauthorized, minor accounts, constituting more than 15% of all the retweets. This consists of influencer content (travel recommendations, lifestyle) and political commentary. The retweeted content also includes posts from Chinese journalists, who run private accounts and have not been marked ‘state-affiliated’.

Post retweeted by the Chinese Embassy suggesting the lavish lifestyle of the Uyghur minority. The original post was from twitter account @Sky_Blue168, which is suspended by Twitter.

Private profile of CCTV Journalist, often retweeted by the Chinese Embassy to France.