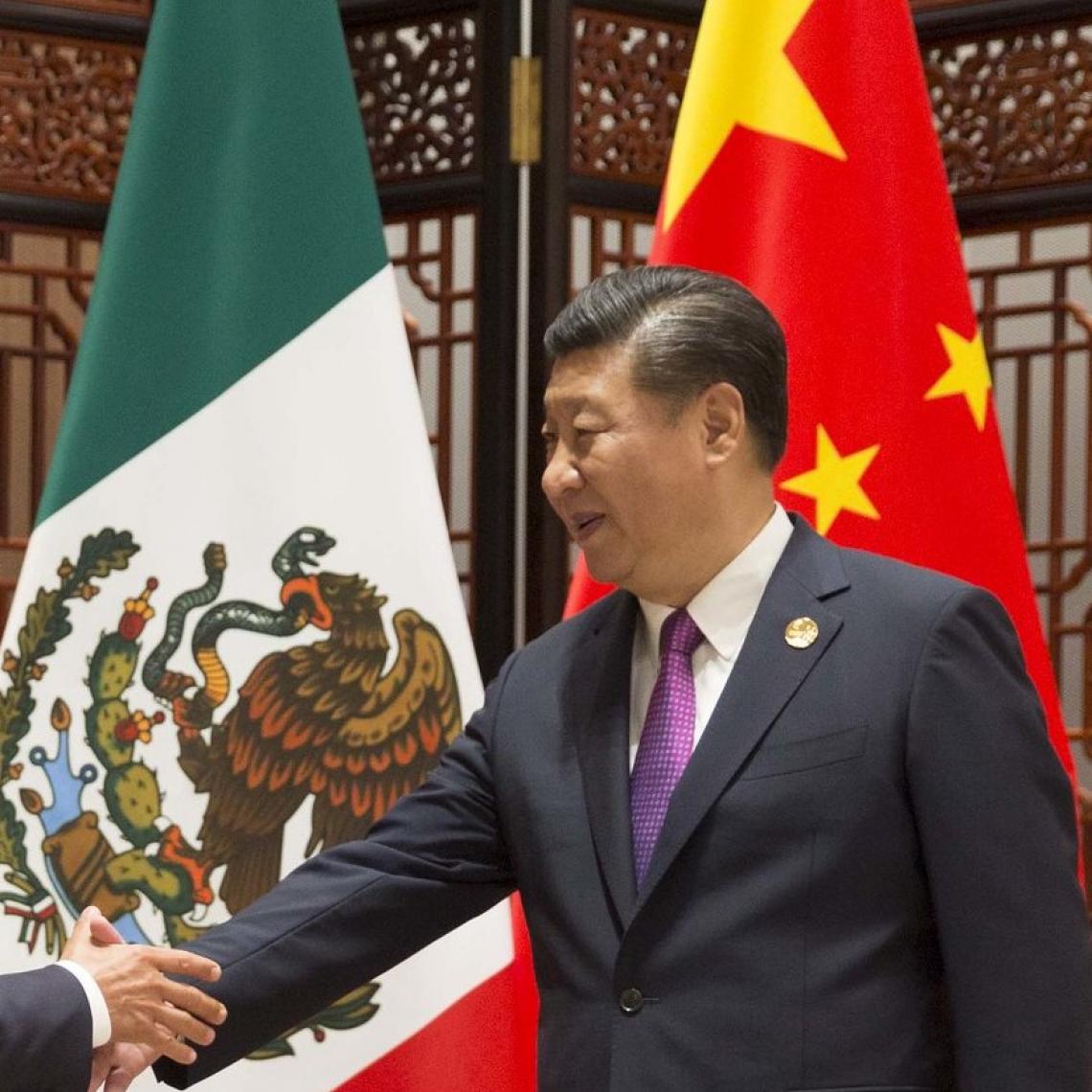

Xi Jinping in June 2018. Image from "Archive: US Secretary of State," available at Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.

The Birth of a Foreign Policy Catchphrase

The journey of “community of common destiny” to the center of China’s foreign policy lexicon has been years in the making.

Over the past few years, the phrase “community of common destiny for mankind,” or renlei mingyun gongtongti (人类命运共同体), which made its first official appearance in the political report to the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, has come to play a central role in China’s political discourse. Last December, when Yaowen Jiaozi (咬文嚼字), a magazine on language published by the Shanghai Cultural Publishing Group, ran its list of the top-ten phrases in 2018, it was “community of common destiny for mankind” that topped the list.

But the journey of this phrase to the centre of Chinese political discourse has been years in the making. In 2013 and 2014, “community of common destiny for mankind” did not appear to be of special significance within the larger context of political discourse, and it was only in 2015 that the phrase began heating up. By the second half of that year, this was clearly reflected in the frequency of use of the phrase in the official state media, particularly around Xi Jinping’s September 28 speech at the United Nations, for which the official English-language translation was: “Working Together to Forge a New Partnership of Win-Win Cooperation and Create a Community of Shared Future for Mankind.”

QUICK TAKE

Use of Xi Jinping's new foreign policy catchphrase has steadily increased in official Party media since 2015. But the term has a deeper history through related terms that have wavered between positive and negative.

- In the 1950s and 1960s, the term "community of destiny," forming just part of today's phrase, was introduced to China through translations of Stalin's harsh criticism of the ideas of Austrian social democrat Otto Bauer, who asserted that "nations are but communities of destiny."

- In the 1960s and 1970s, during the Cultural Revolution, "community of destiny" was used in the context of China's criticism of close relations between Japan and South Korea.

- In 1977, after the Cultural Revolution, in an ice-breaking reference to Sino-Japanese relations, the People's Daily quoted Japanese Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda as saying that "Japan and China are a community of destiny traveling in the same boat."

- In 2009, soon after the election of Barack Obama, the People's Daily reported that former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had "called on China and the United States to build a 'community of common destiny.'"

The reader will notice that the English translation of Xi Jinping’s UN speech uses the word “future” instead of “destiny” to translate this phrase. “Destiny,” in fact, is a much closer translation of the Chinese word mingyun (命运), which can also be rendered as “fate.” But as the phrase was introduced as a core foreign relations concept beyond China’s domestic media sphere, Chinese diplomats apparently realized that ideas of “fate” and “destiny” might have uncomfortable connotations. I leave it to my European colleagues to address the possible connotations in their own languages, and how the phrase has or has not been accepted.

From 2015 onward, it became clear that “community of common destiny for mankind” — I will preference the use of “destiny” over “future” — was meant to play a central role in Chinese foreign policy. In his UN speech, Xi Jinping called on the countries of the world to “build a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation, and create a community of shared future for mankind.”

From 2015 onward, it became clear that “community of common destiny for mankind” was meant to play a central role in Chinese foreign policy.

By 2016 the phrase was moving from visibility to prominence in China’s media, and by 2017 its use was practically ubiquitous, making it one of the most frequently used terminologies within the political discourse of the CCP. In an online collection of the “important speeches” of Xi Jinping in 2017, the rate of usage of “community of common destiny for mankind” surpassed even the use of “Belt and Road,” referring to China’s global infrastructure initiative. And by 2017, the phrase was generating some attention internationally — among those, at least, who closely followed China’s international relations.

In this article, I will explore the origins of the phrase “community of common destiny for mankind” within the context of Chinese political discourse. How did this phrase emerge? When exactly did it emerge? How have the associated meanings changed over time?

Community and Destiny

Let’s begin by pulling the constituent parts of this phrase apart. The term “community of destiny,” or mingyun gongtongti (命运共同体), first appeared in published materials in mainland China in the 1950s. We find it in the Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper even before the start of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. At that time, the phrase was used in a very critical way, implying censure.

At a more basic level, the word “destiny,” or mingyun (命运), can be found in classical Chinese, used to express the idea that “Heaven” (天), a higher power, determine’s fate. In modern vernacular speech, “destiny” simply means submission to a higher will, or the resigning of oneself to fate — what in Chinese is called tingtian youming (听天由命), where the subject is in a passive role.

In the first half of the 20th century, however, political figures in China began using the idea of “destiny” in a different way.

Mao Zedong’s speech on the opening of the 7th National Congress of the Chinese Community Party in 1945, toward the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, was titled “Two Chinese Destinies” (两个中国之命运). In that speech, Mao said: “Two roads stretch out before the people of China, the road of light and the road of darkness. There are two Chinese destinies, the Chinese destiny of light, and the Chinese destiny of darkness.” Darkness referred to the dictatorship of the Kuomintang, and light referred, by implication, to the freedom and democracy ostensibly on offer by the Chinese Communist Party. Mao’s notion of “destiny” bore no spiritual connotations.

The word “community,” or gongtongti (共同体), is a relatively recent addition to the Chinese language. Where did it come from?

In fact, Marx and Engels frequently used the word “community,” or Gemeinschaft, in their writings. Discussing the phrase “community of common destiny for mankind” last year, sleuthing Chinese internet users pointed out that the word “community,” gongtongti, appears in the Chinese-language translation of the Communist Manifesto. In The German Ideology (德意志意识形态), written in 1846 but not published until the 1930s, Marx and Engels also wrote:

In der wirklichen Gemeinschaft erlangen die Individuen in und durch ihre Assoziation zugleich ihre Freiheit.

In English translation, this has been rendered as follows:

In a real community the individuals obtain their freedom in and through their association.

And sometime during the first half of the 20th century, this was translated into Chinese as follows (our emphasis on the word “community”):

在真正的共同体中, 个体通过联合并且在联合中同时也取得自由.

Considering that Chinese translations of The Communist Manifesto and The German Ideology were already available by the middle of the 20th century, we might surmise that the word “community,” or gongtongti, appeared earlier still.

An article in Academic Journal of Law and Politics (法政学报), dating back to 1925, uses the word “community.”

In the archives of the Shanghai Library, I stumbled recently across a copy of the Academic Journal of Law and Politics (法政学报) dated 1925 that included the word in a headline. The article in question is attributed in the text to an original from the Japanese language — so we might suppose that “community,” like many neologisms in Chinese at that time, was introduced from Japanese.

“Destiny” + “Community”

The term “community of destiny” does appear in German as Shicksalsgemeinschaft, and this phrase made its way to China through a book by Josef Stalin.

Some might suggest similar phrases dating back to the Republic Era. In his 1943 book China’s Destiny (中国之命运), for example, Chiang Kai-shek does use the phrase “common destiny,” or gongtong de mingyun (共同的命运), referring to ethnic relations within China. But I was unable to locate, in the limited databases available to me, any mention in the Republican Era of the phrase “community of destiny.”

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, however, many of Stalin’s works were translated into Chinese, and it is in his Marxism and the National Question (马克思主义与民族问题) that we find Stalin roundly criticising the phrase “community of destiny.”

The target of Stalin’s outrage was Otto Bauer, an Austrian Social Democratic regarded at the time as a leading Marxist thinker. Bauer had written a book called The Question of Nationalism and Social Democracies, in which he asserted that “nations are but communities of destiny.” Stalin dismissed this notion as “idealism.”

There is no sense in getting into the finer points of this debate. Suffice to say that wee can establish the entry of the phrase “community of destiny” into China soon after 1949 can be well established. On June 12, 1953, the People’s Daily published an article commemorating the 40th anniversary of the publication of Marxism and the National Question. The article revisited the debate between Stalin and Bauer, but the phrase used in this case was “common destiny,” not “community of destiny.”

It was on was December 22, 1965, that the full phrase “community of destiny” appeared for the first time in the People’s Daily. A dispatch in the paper from the official Xinhua News Agency telegraphed fierce North Korean opposition to the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, which had been signed in June that year, establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea. In describing the import of the treaty, the news story from Xinhua mentioned that the two sides wished to form a “community of destiny between Japan and Korea” (日韩命运共同体).

“Community of destiny” appeared just twice before the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. The second appearance was on May 25, 1970, again in a Xinhua News Agency report sharply criticising the notion of a “community of destiny between Japan and Korea.”

Through the Cultural Revolution, we can find references in the People’s Daily to this or that “community” on the international stage. There is talk of the French Community (法兰西共同体), an association of former French colonies, of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (中美洲共同体), and so on. Toward most of these communities, China maintains a cautious and observational distance. But those viewed as constituting a threat to Chinese interests, like the idea of a “community of destiny between Japan and Korea,” are treated with unmistakable enmity.

But in 1977, just one year after the end of the Cultural Revolution, China suddenly found itself part of its own “community of destiny between China and Japan” (中日命运共同体), something previously unimaginable. Sino-US and Sino-Japanese relations were gradually on the mend toward the middle and end of the Cultural Revolution, and soon after relations entered a honeymoon period. The ice was broken further in October 1977 when a delegation of Chinese journalists traveled to Japan. Meeting with the delegation, Japanese Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda said: “Japan and China are a community of destiny traveling in the same boat.” This account appears in the People’s Daily on December 8, 1977, in an article called, “Sino-Japanese Friendship is the Historical Trend” (中日友好是历史潮流).

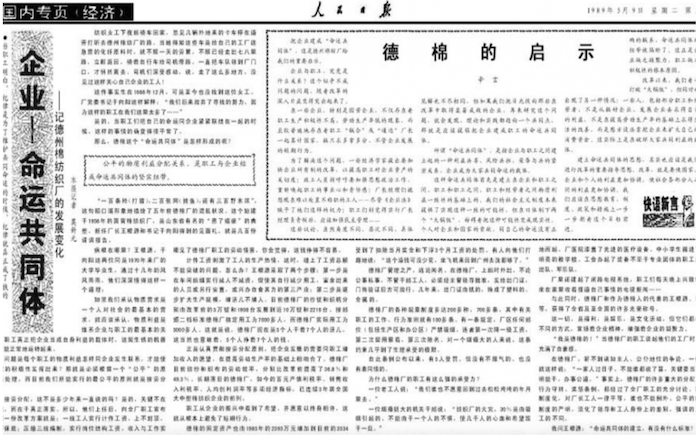

By the 1980s we find the word “community” appearing more frequently in the People’s Daily, chiefly in reports about the impact of economic reforms that focus on the relationships between various economic interests. And we begin also to see references to “community of destiny.” A report about Japanese companies and farmers in 1981, for example, talks about the formation of “communities of destiny” — basically, economic relationships that are of mutual benefit. Another report in 1984 explains how Japanese companies are trying to raise the sense of belonging among workers in order to create a “community of destiny.” As the People’s Daily reported in 1989 on the development of cotton processing factories in the city of Dezhou, the phrase “community of destiny” made its first headline appearance in the paper.

The People’s Daily in 1989 includes a headline with the term “community of destiny,” referring to the enterprise sector. Source: People’s Daily archives.